Design thinking is getting a lot of attention in some education and business circles these days. More people are realizing the importance of putting the user at the center of the design process to ensure whatever is being made meets their actual and not perceived needs. Quality education experiences likewise require program staff to design for specific contexts.

Working with so many different types of people—classroom teachers, museum educators, library patrons and the general public—means that we get the opportunity to examine crafting creative learning experiences from many different perspectives. The result is the ability to apply the insights unique to each group and use them to benefit how we design for the others. As we gather more information about what works and what doesn't, we are able to iterate and improve upon materials and activity structures to provide the most engaging experiences possible.

In our ramp up for Hack Your Notebook Day, we took the opportunity to test out prototype materials with two groups: pre-service museum educators and library patrons.

JFK University, Museum Studies Program

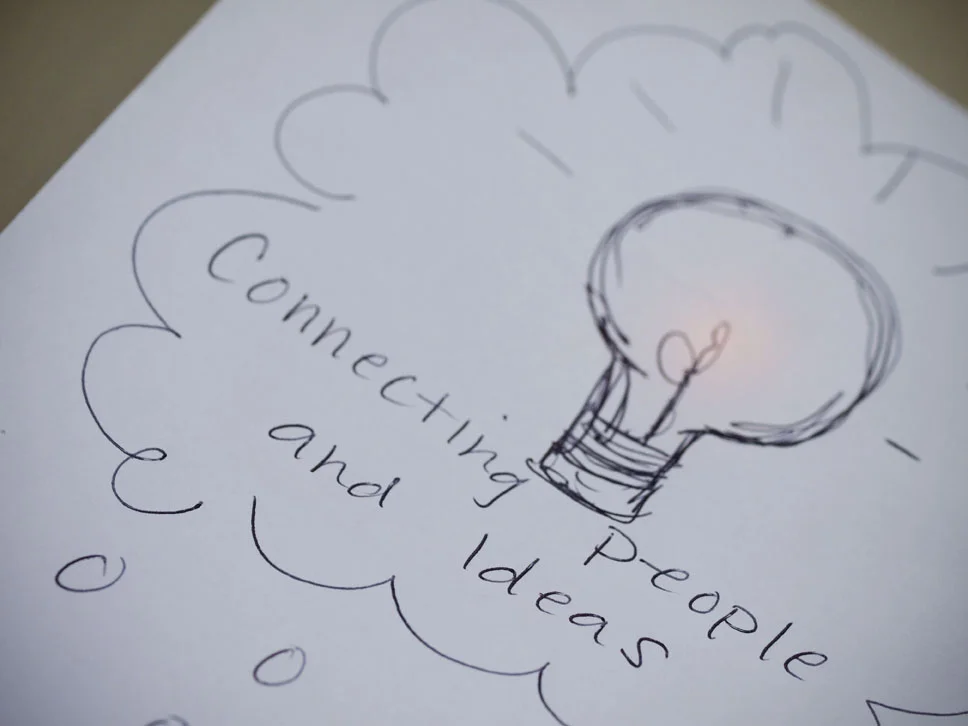

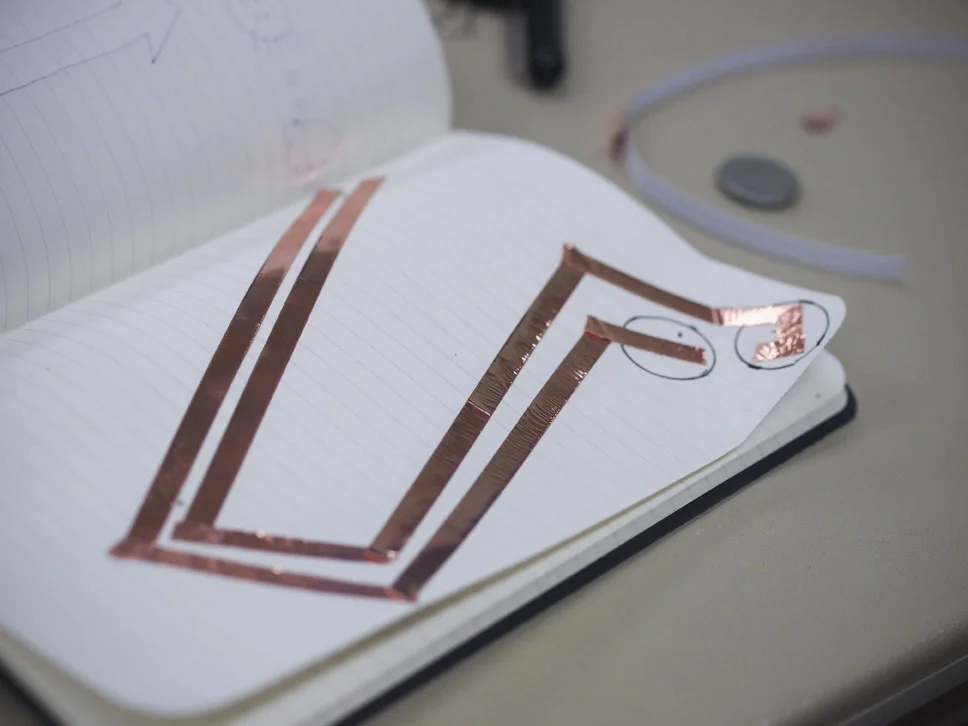

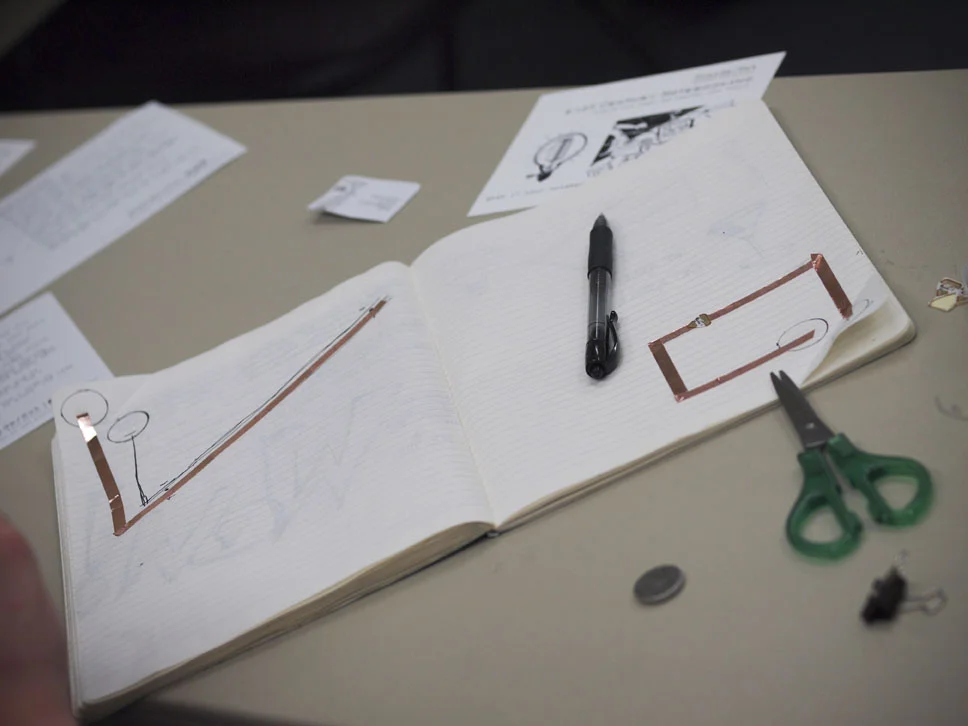

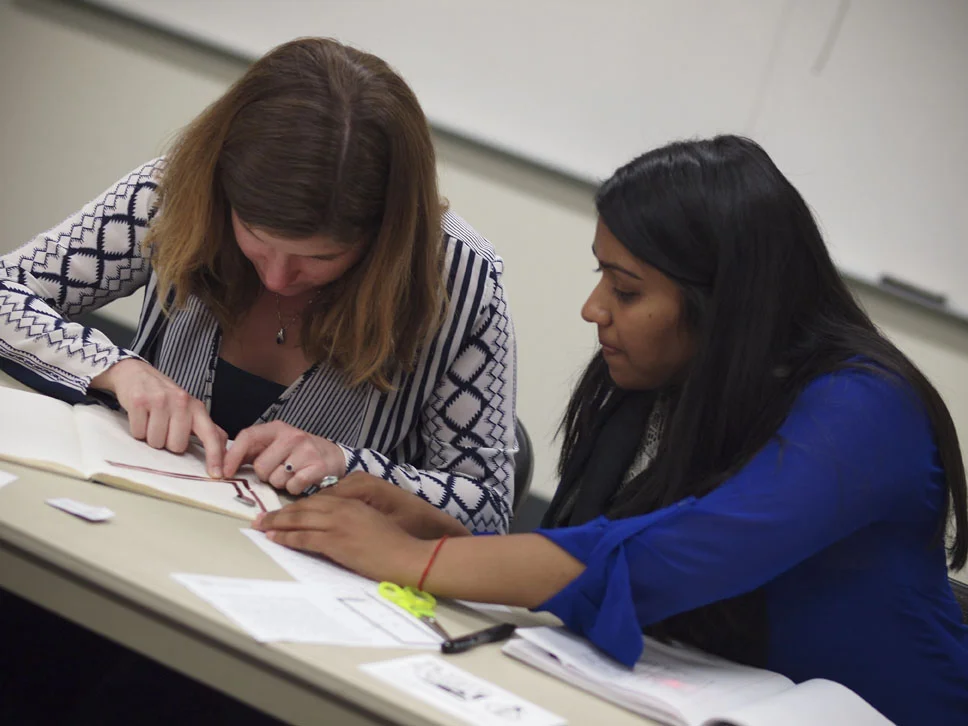

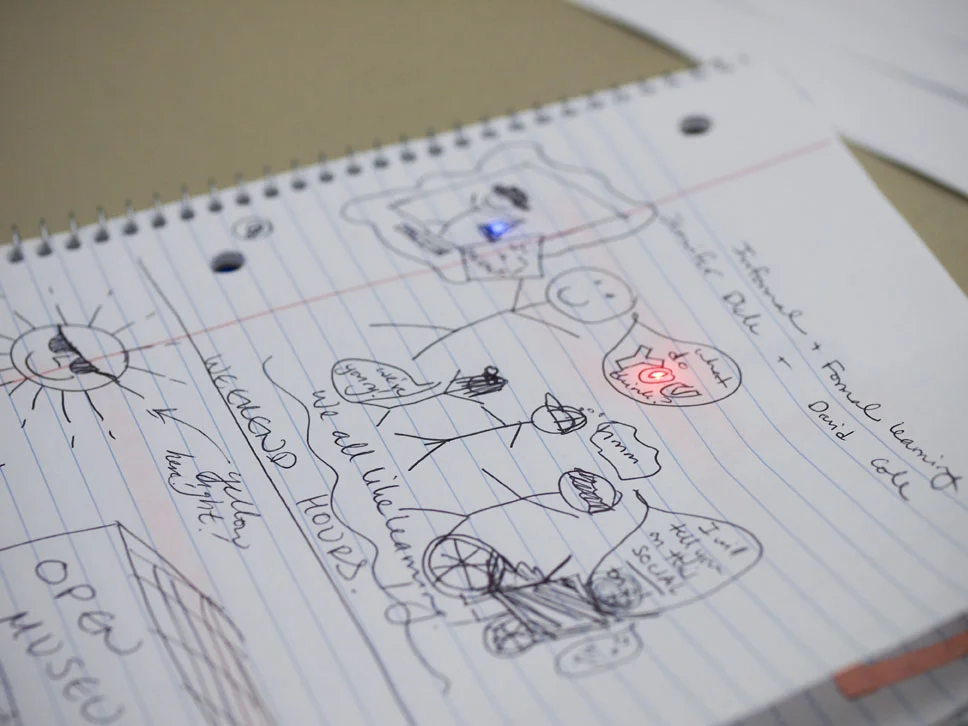

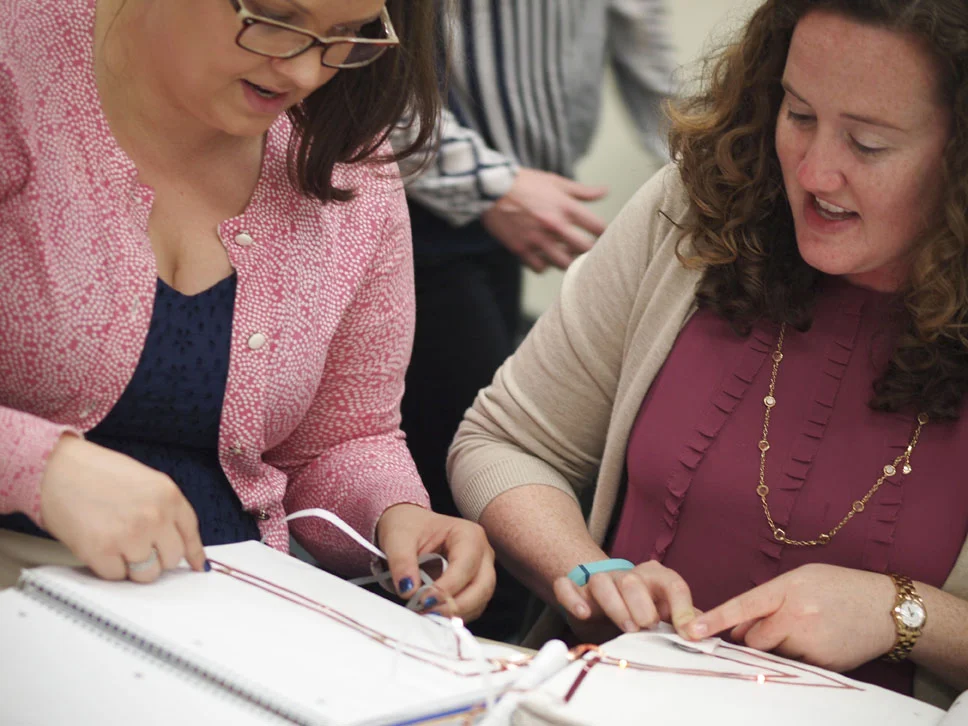

On Tuesday, May 20th, David Cole of CV2 and I had the pleasure of running a paper circuitry workshop with Dr. Susan Spero’s Visitor Experience class using the step-by-step activity cards we'd mocked up. Being able to work with this group was great for a couple of reasons: they'd recently visited the Exploratorium’s Tinkering Studio where they'd had a circuit-based activity experience and they're studying activity design for informal spaces. Given that they'd recently worked with the concept of circuit-building, this let them focus on working with new materials (copper tape and circuit stickers) and the clarity of the supporting resources and activity structure.

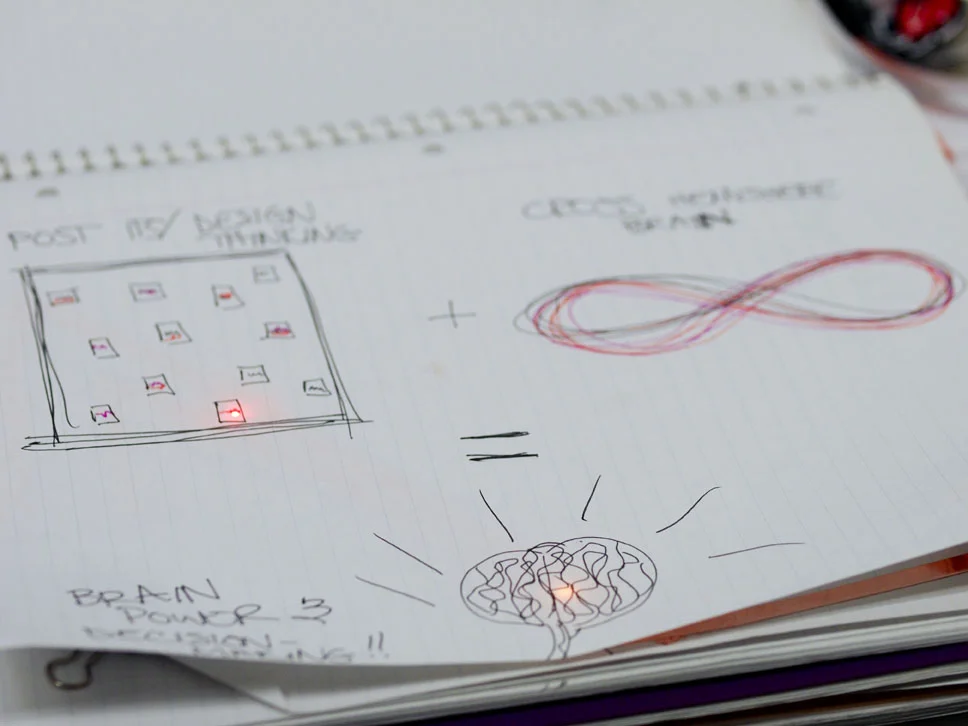

Because if their feedback, we were able to rework the activity cards completely. We moved from a two-sided half-sheet to a full sheet, re-ordered the information presented on the card and revised some of the language to increase clarity. We also heard great ideas for alternate ways to support a more discovery-based experience appropriate for museum spaces.

This lead to a more general conversation about the design process and accepting feedback. Some of the students were hesitant to be critical at first in their comments, fearing that we’d be hurt or offended by hearing about things they didn't think worked perfectly. It’s critical (ahem) to be able to accept criticism if you want to deliver the best for your constituents. A great strength of taking a design thinking approach to program design is that failure is expected: things that aren’t working or are not optimal are seen as opportunities for growth and not a negative judgment on the creators. Many of us have been taught to be fearful of critique, but artists and scientists alike know it’s an essential part of the process.

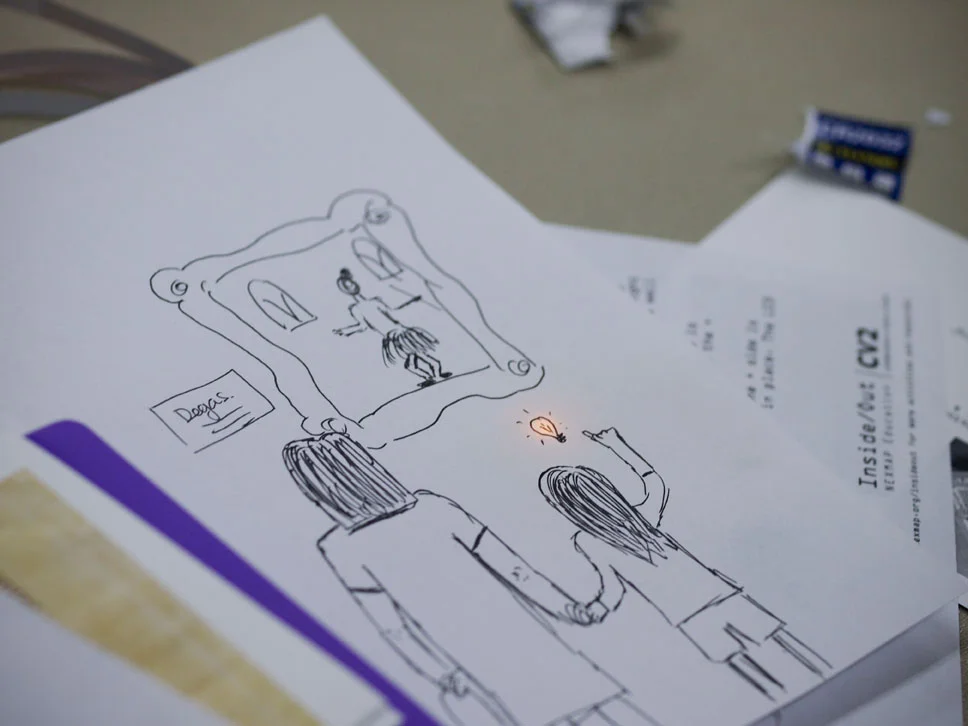

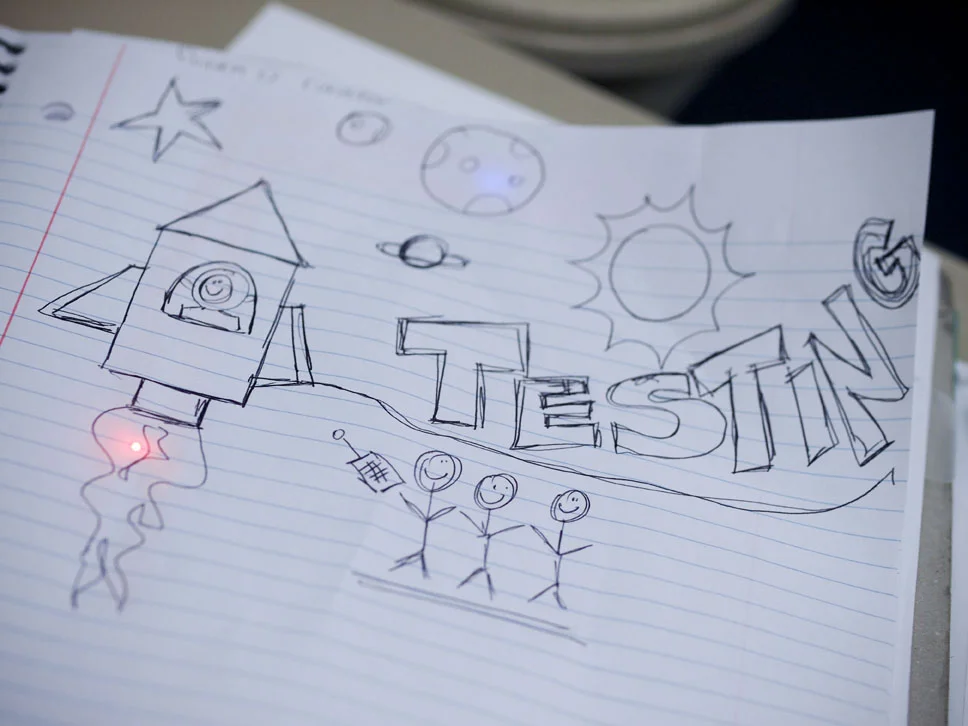

Mountain View Public Library

That Saturday, May 24th, David and I went down to Mountain View Public Library to work with a very different group in a very different context. As part of the library’s Star Wars-themed day, we set up a maker table where visitors were invited to create light-up sci-fi themed cards. Most participants were families with young children. The card worksheet we used were the second iteration of those we used at the San Jose Public Library a couple of months ago. We noticed that few people read the directions in the first version, so we shorted the text significantly and labeled the circuit template to reference the instructions. We also adjusted the template to more clearly depict the copper tape going inside the battery circles and underneath the circuit sticker.

Although the activity was fairly simple and most succeeded with their first try, we were able to see patterns of common issues encountered by makers (tape joins, circuit sticker contacts). We also were able to see issues unique to the much younger makers (some were as young as 4 years old). For example, 1/8” copper tape is really hard for young fingers to work with—even ¼” can be tricky to handle.

Each program has its own unique context and therefore its own unique needs, but by continuing to engage with a diverse group of participants, we get closer and closer to being able to deliver universally satisfying creative learning experiences.